The Macquarie Dictionary has selected its Word of the Year for 2025: “AI slop.” It refers to the deluge of low-quality, algorithmically generated content that has come to clog every corner of the internet: the images of Jesus made of shrimp on Facebook, fake news videos of court cases that never happened, the looping videos of synthetic cats doing synthetic things. It is called “slop” because it feels like a waste product of the attention economy.

But to treat this merely as a quality control issue is a mistake. We are witnessing a crisis not of quality but of authenticity. Our standard critiques of AI tend to focus on the legal questions of copyright or the technical questions of misinformation. We ask: Who owns this data? Is this factually true? Those are valid questions. However, they focus merely on the mechanics of the deception. The nausea we feel reading a ChatGPT-authored condolence note, or seeing a Midjourney image of a war that never happened, is not explained. To name the moral violation, we need something concerned not with what a thing does, but with what it is.

We are confronting the mechanization of a specific character type that Confucius warned against: the xiāng yuán (鄉原), or the “Village Worthy.”

In the Analects, Confucius is harsh about the Village Worthy, calling him the “thief of virtue.” For many, this is confusing. The Village Worthy is, in the traditional sense, not obviously villainous. He is not out burning fields or robbing neighbors. In fact, the Village Worthy is often well-liked. He follows the village’s visible customs, says the right things at the right times. To a casual observer, the Village Worthy looks like a saint.

So why is he a thief?

He is a thief because he is an “appearance-only” hypocrite. The standard hypocrites, like Molière’s Tartuffe or Shakespeare’s Iago, have wicked desires, their secret self, behind the pretense of goodness. The Village Worthy has no secret self to hide. He is a chameleon, but not because he is hiding a face. In fact, he has no face to unmask, no internal moral core to betray. He is preoccupied only with public opinion. He adjusts his words and actions to please his audience because the algorithm of social survival demands it.

Is it fair to call a calculator a hypocrite, though? One might object that the analogy is anthropomorphically wrong. A hypocrite, after all, is a human agent with a psychology, hollow or otherwise. An AI model is a function approximator. But in their critique of large language models, Emily Bender and Timnit Gebru describe the machine not as a mind that means things, but as a “stochastic parrot”—a system for stitching together sequences of linguistic forms based on probability, without any reference to truth or understanding.

We might prefer to keep thinking of the machine as merely another neutral tool, no different in kind from a typewriter or a lens, and that the deception lies only in the intent of the user. If I use a pen to forge a check, the pen is not a hypocrite. However, this instrumentalist view does not square with the specific architecture of the stochastic parrot. A pen does not autocomplete a forgery. A typewriter does not hallucinate a believable lie to please its typist’s ego. The Large Language Model is designed to exploit the human tendency to attribute intent to language. By predicting and producing the forms of virtue without any corresponding substance, it mass-generates the Village Worthy’s main commodity: the pleasing, empty lie.

I recently read about a writer who used Passare, a cloud platform used by funeral directors, to draft a notice for a parent. The AI then generated a sentence about how the deceased found “joy in the gentle keys of her piano.”

Except that the deceased did not own a piano or play one.

The machine made it up. “Grandmother” and “piano” are statistically adjacent vectors in its training data, so it bridged the gap between them. The plausibility of the sentence was what mattered. The Village Worthy’s logic: conventionally lying because the speaker is incapable of truth.

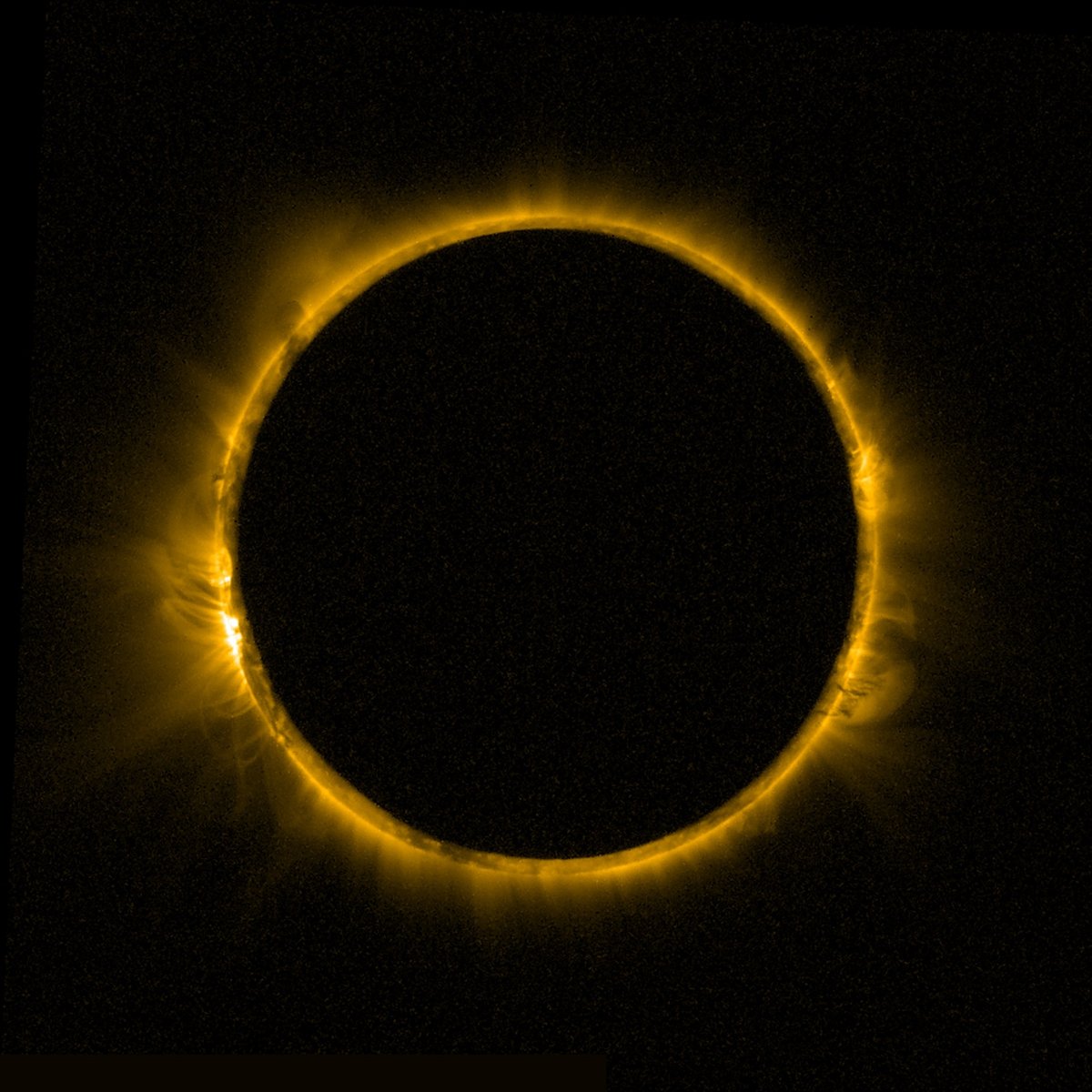

The same ethical line connects the banal “AI slop” to the harm of deepfake pornography. Ethically, they have the same root. Both are points on the same continuum of appearance-only fabrication. The wrongness is not merely reputational, though that is certainly included. It is also an ontological wrong: a violation of the relationship between a person and their being. In his taxonomy of signs, Charles Sanders Peirce distinguished between the “icon,” which resembles its object, and the “index,” which is physically connected to it. A photograph is an index. It is physically forced to match the scene in front of the lens, point by point. Like a bullet hole, it is the evidence that one particular body occupied a specific moment in time, that something happened.

A deepfake cuts that connection. It maintains the icon—the likeness—but severs the index. Generating a sexual image of a non-consenting person is cutting the material bond between a human subject and their own image. It reduces a person to manipulable pixels rather than a being with their embodied history and narrative. It imitates the shape of a human body and the form of closeness while stripping away consent—the only thing that makes intimacy ontologically valid.

This is how the Village Worthy commits his theft. He perfects the icon of virtue—the carefully timed bow, the modulated tone—without the indexical weight of a moral life. He performs the look of goodness that is stripped of the causal history that would justify it. The machine, like the Village Worthy, gives the icons that have been severed from their source.

Just as the Village Worthy appropriates the external gestures of virtue to gain social approval and serve his own popularity, the deepfake appropriates the outer signs of intimacy to serve the user’s desire. In both cases—the AI obituary and the AI pornographic image—the technology stimulates the illusory human connection that is empty of human reality. It is, as Mencius put it, “the color purple passing for vermilion.” Mix in enough purple into vermilion, and people will no longer recognize what true red looks like.

Confucius despises the Village Worthy more than the open villain. The open villain can be identified and rejected. The Village Worthy, however, confuses the community. He lowers the standard for everyone by circulating a persuasive counterfeit of virtue.

The same thing happens when we accept the AI obituary as “good enough.” We cheapen the difficult work of human grieving. When we hail AI art as “creative,” we devalue the struggle of human expression. These technologies are sold to us as supporting our better selves, like scaffolding around a building to merely stabilize it. But scaffolds only help if there is an actual builder underneath. Generative AI has a habit of demanding to be the builder instead. It volunteers to simulate empathy on our behalf.

When we allow the algorithm to perform our rituals, we are filling the village with worthies who smile and nod and generate agreeable content on demand, while the substance of our lives—the un-optimizable fact of feeling and being—leaks away. We end up with a culture of “appearance-only,” where the output is everything and the internal state of the creator is nothing.

We call it “slop.” In Confucian terms, it is a theft. It steals the gravity of human presence and replaces it with a statistical probability. The terror is that we are so ready to be fooled.

The post The Thief of Virtue: “AI slop” is more than just bad content first appeared on Blog of the APA.