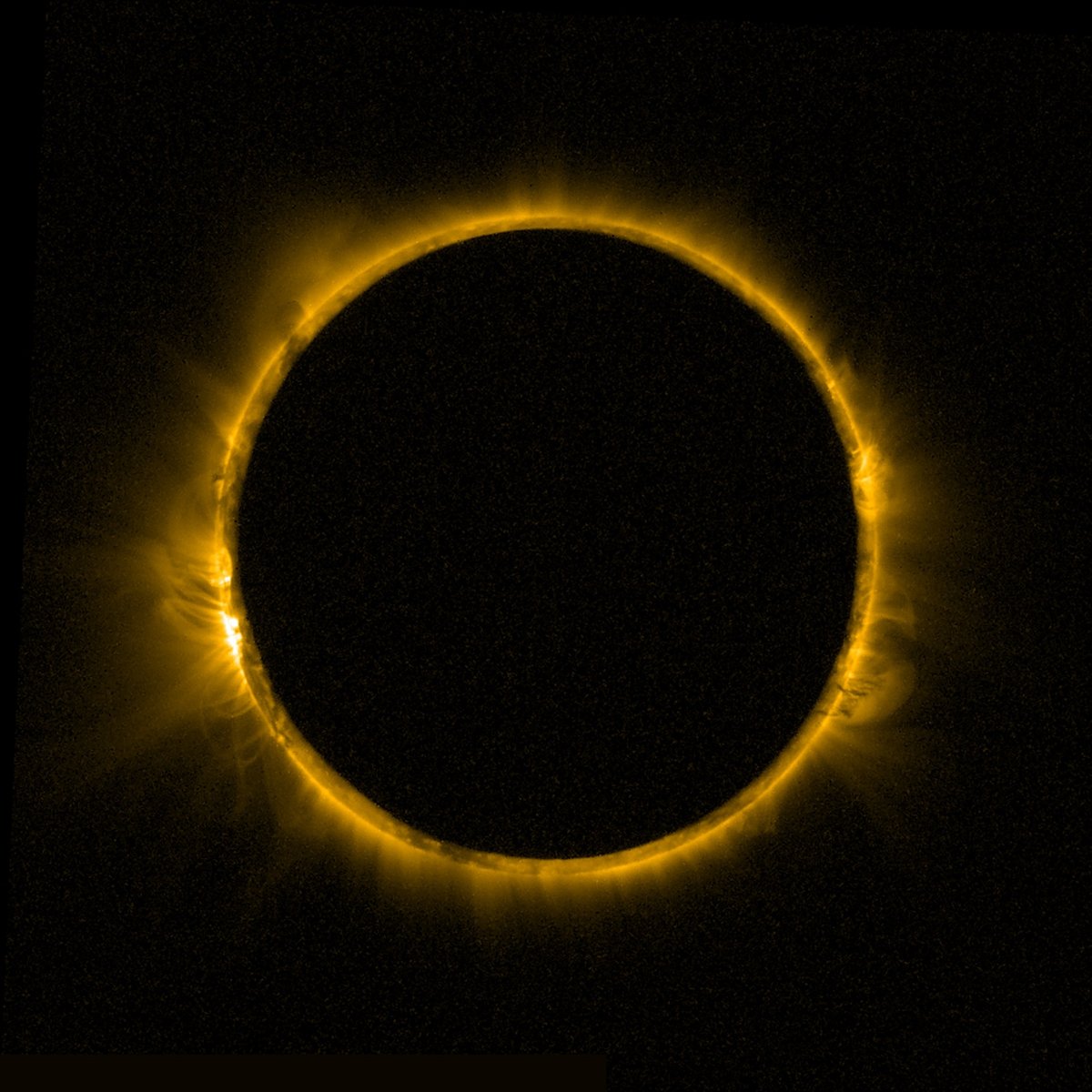

During the recent annular solar eclipse on February 17, the ESA’s PROBA-2 satellite captured this great shot of the Moon passing in front of the Sun. Cue up the Johnny Cash.

Tags: astronomy · Moon · photography · science · Sun

During the recent annular solar eclipse on February 17, the ESA’s PROBA-2 satellite captured this great shot of the Moon passing in front of the Sun. Cue up the Johnny Cash.

Tags: astronomy · Moon · photography · science · Sun

Photo by Leila Navidi/The Minnesota Star Tribune via Getty Images

Photo by Leila Navidi/The Minnesota Star Tribune via Getty Images Earlier this week, an unexpected and fast-moving incident unfolded in St. Paul, Minnesota involving both federal and local law enforcement. As crowds gathered and questions mounted, one of our MPR News reporters, Sam Stroozas, realized she lived just blocks away.

She did what reporters do.

She went.

There wasn’t time to change clothes. Sam arrived in a bathrobe and slippers and began reporting from the scene.

A photo captured the moment. It circulated quickly across local media and online, sparking conversation — and, overwhelmingly, appreciation for Minnesota’s “Bathrobe Lady.”

But the reaction wasn’t really about the bathrobe.

It was about what it represented.

Local journalism often begins before a camera is rolling, before a live shot is framed, before a headline is written. It begins with proximity. With awareness. With someone deciding that what’s happening matters enough to go see it firsthand.

It begins with showing up.

That instinct, to move toward the story, not away from it, is shared across our newsroom. Reporters, producers, editors, photographers and engineers regularly respond in real time when news breaks. They work evenings, early mornings and weekends. They field tips, verify information, and help provide clarity in moments that can quickly become confusing or chaotic.

Sometimes, that work looks polished and composed on air.

Sometimes, it starts in slippers.

Later this week, colleagues across the organization wore robes to the office as a lighthearted tribute to Sam and to the broader newsroom. It was a small, communal way to recognize something serious: the commitment to being present for Minnesota communities when it matters most.

Journalism is built on preparation, rigor and accountability. It is also built on people — people who live in the neighborhoods they cover, who are part of the communities they report on, and who care deeply about getting the story right.

This week’s moment offered a glimpse behind the scenes. A reminder that before the microphones, the editing bays and the published stories, there are human beings not only paying attention, but working to get the trusted facts to the community serve every day.

And when news breaks close to home, they go.

"Saw the Sam Stroozas photo. Now that is dedicated community journalism." –John in St. Paul

"Sam Stroozas recording ICE officers with her neighbors in her bathrobe and slippers brought tears to my eyes." –Ted

"Thank you to you all… Especially the Bathrobe Lady It’s been a rough ride here in the cities." –Robert in St. Paul

Explore MPR News

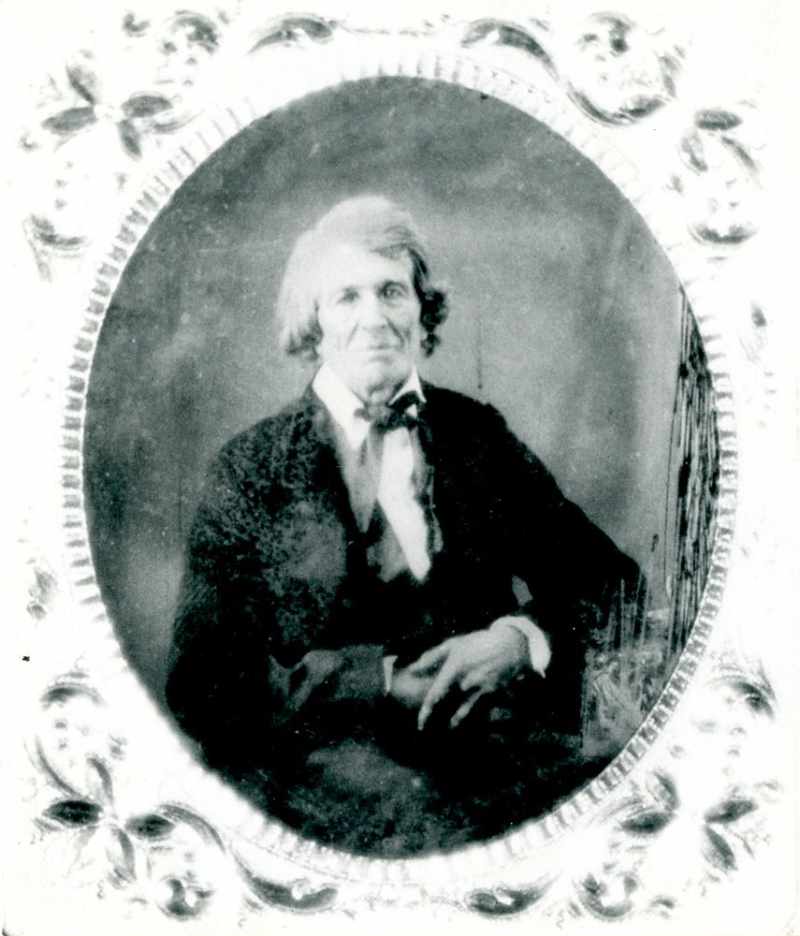

John Owen, one of the last veterans of the French and Indian War, lived to be 107 and posed for this photograph shortly before his death in 1843.

That makes him one of the earliest-born humans ever to be photographed. He was born in 1735.

Hovertext:

Personally, I transsubstantiate every kitkat I eat.

Photographs by Jack Califano

It took only a few minutes before everyone in the church knew that another person had been shot. I was sitting with Trygve Olsen, a big man in a wool hat and puffy vest, who lifted his phone to show me a text with the news. It was his 50th birthday, and one of the coldest days of the year. I asked him whether he was doing anything special to celebrate. “What should I be doing?” he replied. “Should I sit at home and open presents? This is where I’m supposed to be.”

He had come to Iglesia Cristiana La Viña Burnsville, about 15 miles south of the Twin Cities, to pick up food for families who are too afraid to go out—some have barely left home since federal immigration agents deployed to Minnesota two months ago. The church was filled with pallets of frozen meat and vegetables, diapers, fruit, and toilet paper. Outside, a man wearing a leather biker vest bearing the insignia of the Latin American Motorcycle Association, his blond beard flecked with ice crystals, directed a line of cars through the snow.

The man who had been shot—fatally, we later learned—was Alex Pretti, an ICU nurse who had been recording agents outside a donut shop. Officials at the Department of Homeland Security claimed that he had threatened agents with a gun; videos of the shooting show him holding only his phone when he is pushed down by masked federal agents and beaten, his licensed sidearm removed from its holster by one agent before another unloads several shots into his back. Pretti’s death was a reminder—if anyone in Minnesota still needed one—that people had reason to be hiding, and that those trying to help them, protect them, or protest on their behalf had reason to be scared.

The church has a mostly Hispanic and working-class flock. Its pastor, Miguel Aviles, who goes by Pastor Miguel, told me that it had sent out about 2,000 packages of food since the federal agents had arrived. Many of the people in hiding, he said, “have asylum cases pending. They already have work permits and stuff, but some of them are legal residents and still they’re afraid to go out. Because of their skin color, they are afraid to go out.”

Federal agents have arrested about 3,000 people in the state, but they have released the names of only about 240 of those detained, leaving unclear how many of the larger number have committed any crimes. Many more thousands of people have been affected by the arrests and the fear they have instilled. Minneapolis Public Radio estimates that in school districts “with widespread federal activity, as many as 20 to 40 percent of students have been absent in recent weeks.”

I don’t know what the feds expected when they surged into Minnesota. In late November, The New York Times reported on a public-benefit fraud scheme in the state that was executed mainly by people of Somali descent. Federal prosecutors under the Biden administration had already indicted dozens of people, but after the Times story broke, President Trump began ranting about Somalis, whom he referred to as “garbage”; declared that he didn’t want Somali immigrants in the country; and announced that he was sending thousands of armed federal immigration agents to Minneapolis. This weekend, he posted on social media that the agents were there because of “massive monetary fraud.” The real reason may be that a majority of Minnesotans did not vote for him. Trump has said that “I won Minnesota three times, and I didn’t get credit for it. That’s a crooked state.” He has never won Minnesota.

Perhaps the Trump-administration officials had hoped that a few rabble-rousers would get violent, justifying the kind of crackdown he seems to fantasize about. Maybe they had assumed that they would find only a caricature of “the resistance”—people who seethed about Trump online but would be unwilling to do anything to defend themselves against him.

Instead, what they discovered in the frozen North was something different: a real resistance, broad and organized and overwhelmingly nonviolent, the kind of movement that emerges only under sustained attacks by an oppressive state. Tens of thousands of volunteers—at the very least—are risking their safety to defend their neighbors and their freedom. They aren’t looking for attention or likes on social media. Unless they are killed by federal agents, as Pretti and Renee Good were, other activists do not even necessarily know their names. Many use a handle or code name out of fear of government retaliation. Their concerns are justified: A number of people working as volunteers or observers told me that they had been trailed home by ICE agents, and some of their communications have already been infiltrated, screenshotted, and posted online, forcing them to use new text chains and code names. One urgent question among observers, as the videos of Pretti’s killing spread, was what his handle might have been.

Olsen had originally used the handle “Redbear” in communicating with me, but later said I could name him. He had agreed to let me ride along while he did his deliveries. As he loaded up his truck with supplies, he wore just a long-sleeved red shirt and vest, apparently unfazed by the Minnesota cold.

“This is my first occupation,” Olsen said as I climbed into the truck. “Welcome to the underground, I guess.”

The number of Minnesotans resisting the federal occupation is so large that relatively few could be characterized as career activists. They are ordinary Americans—people with jobs, moms and dads, friends and neighbors. They can be divided into roughly three groups.

The largest is the protesters, who show up at events such as Friday’s march in downtown Minneapolis, and at the airport, where deportation flights take off. Many protesters have faced tear gas and pepper spray, and below-zero temperatures—during the Twin Cities march on Friday, I couldn’t take notes; the ink in my pens had frozen.

Then there are the people who load up their car with food, toiletries, and school supplies from churches or schools to take to families in hiding. They also help families who cannot work meet their rent or mortgage payments. In addition to driving around with Olsen, I rode along with a Twin Cities mom of young kids named Amanda as she did deliveries (she asked me to use only her first name). Riding in her small car—her back row was taken up by three child seats and a smattering of stray toys—she told me that she’d gotten involved after more than 100 students at her kids’ elementary school simply stopped coming in. Parents got organized to provide the families with food, to shepherd their kids to school, and to arrange playdates for those stuck inside.

Amanda’s father and husband are immigrants, she said, and she speaks Spanish. “I can be a conduit between those who want to help and those who need help,” she told me. She calls each family before knocking on the door, so they don’t have to worry that they are being tricked by ICE. At one home, a woman asked us to go around back because a suspicious vehicle was idling out front. At another home, a little girl in pigtails beamed as Amanda handed her a Target bag full of school supplies.

Finally, there’s those most at risk of coming into violent contact with federal agents, a group that’s come to be popularly known as ICE Watch, although the designation is unofficial—as far as I can tell, you’re in ICE Watch if you watch ICE. These are the whistle-wielding pedestrians and drivers calling themselves “observers” or “commuters” who patrol for federal agents (usually identifiable by their SUVs with out-of-state plates) and alert the neighborhood to their presence. Pretti and Good, the two Minneapolis residents killed by federal agents, fit in this category.

Trump-administration officials and MAGA influencers have repeatedly called these activists “violent” and said they are involved in “riots.” But the resistance in Minnesota is largely characterized by a conscious, strategic absence of physical confrontation. Activists have made the decision to emphasize protection, aid, and observation. When matters escalate, it is usually the choice of the federal agents. Of the three homicides in Minneapolis this year, two were committed by federal agents.

“There’s been an incredible, incredible response from the community. I’ve seen our neighbors go straight from allies to family—more than family—checking in on each other, offering food and rides for kids and all kinds of support, alerting each other if there’s ICE or any kind of danger,” Malika Dahir, a local activist of Somali descent, told me.

If the Minnesota resistance has an overarching ideology, you could call it “neighborism”—a commitment to protecting the people around you, no matter who they are or where they came from. The contrast with the philosophy guiding the Trump administration couldn’t be more extreme. Vice President Vance has said that “it is totally reasonable and acceptable for American citizens to look at their next-door neighbors and say, ‘I want to live next to people who I have something in common with. I don’t want to live next to four families of strangers.’” Minnesotans are insisting that their neighbors are their neighbors whether they were born in Minneapolis or Mogadishu. That is, arguably, a deeply Christian philosophy, one apparently loathed by some of the most powerful Christians in America.

On Wednesday, I met with two volunteers who went by the handles “Green Bean” and “Cobalt.” They picked me up in the parking lot of a Target, not far from where Good was killed two weeks earlier. Cobalt works in tech but has recently been spending more time on patrol than at her day job. Green Bean is a biologist, but she told me the grant that had been funding her work hadn’t been renewed under the Trump administration. Neither of them had imagined doing what they were doing now. “I’m supposed to be creeping around in the woods looking at insects,” Green Bean said.

Most commuters work in pairs—a co-pilot listens in on a dispatcher who provides the locations of ICE encounters and can run plates through a database of cars that federal agents have used in the past. Green Bean explained what happens when they identify an ICE vehicle. (Both ICE and Border Patrol are in Minneapolis, but everyone just calls them ICE.) The commuters will follow the agents, honking loudly, until they leave the neighborhood or stop and get out.

The commuters—as my colleague Robert Worth reported—do not have a centralized leadership but have been trained by local activist groups that have experience from past protests against police killings, and recent immigration-enforcement sweeps in L.A. and Chicago. The observers are taught to conscientiously follow the law, including traffic rules, and to try to avoid physical confrontation with federal agents.

If the agents detain someone, the observers will try to get that person’s name so they can inform the family. But ICE prefers to make arrests—which the ICE Watchers call “abductions”—quietly. More often than not, Green Bean said, when these volunteers draw attention, the agents will “leave rather than dig in.” She added, “They are huge pussies, I will be honest.”

As we cruised through the Powderhorn neighborhood, practically every business had an ICE OUT sign in the window. Graffiti trashing ICE was everywhere, as were posters of Good labeled AMERICAN MOM KILLED BY ICE. Listening to the dispatcher, Cobalt relayed directions to Green Bean about the locations of ICE vehicles, commuters who had been boxed in or threatened by agents, and possible “abductions.”

About 30 minutes into the patrol, Green Bean saw a white Jeep Wagoneer with out-of-state plates and read out the numbers. “Confirmed ICE,” Cobalt said, and we began following the Wagoneer as it drove through the neighborhood. Another car of commuters joined us, making as much noise as possible.

After about 10 minutes, the Wagoneer got onto the highway. Green Bean followed until we could be sure that it wasn’t doubling back to the neighborhood, and then we turned around.

Most encounters with ICE end like that. But sometimes situations deteriorate—as with Good, who was killed while doing a version of what Green Bean and Cobalt were now doing. The task is stressful for the observers, who understand that even minor encounters can turn deadly.

The next day, I drove around with another pair of commuters who went by “Judy” and “Lime.” Both told me they were anti-Zionist Jews who had been involved in pro-Palestinian and Black Lives Matter protests. Lime’s day job is with an abortion-rights organization, and Judy is a rabbi. “I did protective presence in the West Bank,” Lime told me, referring to a form of protest in which activists try to deter settler violence by simply being present in Palestinian communities. “This is very similar.”

About an hour into our drive, we came across an ICE truck. Judy started blaring the horn, and I heard her mutter to herself: “We’re just driving, we’re just driving, which is legal. I hate this.” I asked them both if they were scared. “I do not feel scared, but I probably should,” Lime said.

Judy said she had been out on patrol days after Good was killed, and had gotten boxed in and yelled at by federal agents. “It was very scary,” Judy told me. “Murdering someone definitely works as an intimidation tactic. You just have no idea what is going to happen.” She said that ICE agents had taken a picture of her license plate and then later showed up at her house, leaning out of their car to take another picture—making it clear to Judy that they knew who she was.

Green Bean had told me the same thing—that agents had come to her house, followed her when she left, and then blocked her vehicle and screamed at her to “stop fucking following us. This is your last warning.” Green Bean was able to laugh while retelling this. “I just stared at them until they left,” she said.

We drove past Good’s memorial. Tributes to her—flowers and letters—were still there, covered in a light powder of snow. We didn’t yet know at the time that residents would soon set up another memorial, for Pretti.

The broad nature of the civil resistance in Minnesota should not lead anyone to believe that no one there supports what ICE is doing. Plenty of people do. Trump came close to winning the state in 2024, and many people here, especially outside the Twin Cities, believe the administration’s rhetoric about targeting “the worst of the worst,” despite what the actual statistics reveal.

“You don’t have to go too far south” to find places where Minnesotans “welcome ICE into their restaurants and bars and sort of love what they do,” Tom Jenkins, the lead pastor of Mount Cavalry Lutheran Church in suburban Eagan, which is also helping with food drives, told me. “A lot of people are still cheering ICE on because they don’t think that whatever people are telling them or showing them is real.”

Although most of the coverage has understandably focused on the cities, suburban residents told me that they had seen operations all over the state. “There are mobile homes not far from where I live,” Jenkins said. Agents “were there every day, you know: 10, 15, 20 agents working the bus stops and bus drop-offs.” He added: “They’re all over.”

Even among those involved in opposing ICE in Minnesota, people have a range of political views. The nonviolent nature of the movement, and the focus on caring for neighbors, has drawn in volunteers with many different perspectives on immigration, including people who might have been supportive if the Trump administration’s claims of a targeted effort to deport violent criminals had been sincere.

“One of the things that I believe, and I know most of the Latino community agrees, is that we want the bad people out. We want the criminals out,” Pastor Miguel, who immigrated from Mexico 30 years ago, told me. “All of us came here looking for a better life for us and for our children. So when we have criminals, rapists—when we have people who have done horrible things in our streets, in our communities—we are afraid of them. We don’t want them here.”

The problem is that federal agents are not going after just criminals. Growing distraught, Pastor Miguel said that one of the men who helped organize the food drive, a close friend of his who he believed had legal status, had been picked up by federal agents the day before I visited.

“I just—I didn’t have words,” he said. “And yet I cannot crumble; I cannot fall. Because all these families also need us.”

Two days after Pretti was killed, my colleague Nick Miroff broke the news that Gregory Bovino, the Border Patrol official who had led the operation in Minneapolis, would be leaving the city and replaced by Trump’s border czar, Tom Homan. Bovino, strutting around in body armor or his distinctive long coat, seemed to relish his role as a villain to his critics, encouraging aggressive tactics by federal agents and sometimes engaging in them himself. The day I accompanied Green Bean and Cobalt, Bovino fumbled with a gas canister before throwing it into a sparse crowd of protesters.

Bovino’s departure seemed an admission that Minnesotans aren’t the only Americans who won’t tolerate more deaths at the hands of federal agents. The people of Minnesota have forced the Trump administration into a strategic retreat—one inflicted not as rioters or insurgents, but as neighbors.

After Friday’s protest, when thousands marched in frigid downtown Minneapolis, chanting, “No Trump, no troops, Twin Cities ain’t licking boots!” I spoke with a young protester named Ethan McFarland, who told me that his parents are immigrants from Uganda. He had recently asked his mother to show him her immigration papers, in case she got picked up. This kind of state oppression, he said, is exactly what his mother was “trying to get away from” when she came to the United States.

McFarland’s remarks reminded me of something Stephen Miller, the Trump adviser, had written: “Migrants and their descendants recreate the conditions, and terrors, of their broken homelands.” In Minnesota, the opposite was happening. The “conditions and terrors” of immigrants’ “broken homelands” weren’t being re-created by immigrants. They were being re-created by people like Miller. The immigrants simply have the experience to recognize them.

The federal surge into Minneapolis reflects a series of mistaken MAGA assumptions. The first is the belief that diverse communities aren’t possible: “Social bonds form among people who have something in common,” Vance said in a speech last July. “If you stop importing millions of foreigners into the country, you allow social cohesion to form naturally.” Vance’s remarks are the antithesis to the neighborism of the Twin Cities, whose people do not share the narcissism of being capable of loving only those who are exactly like them.

A second MAGA assumption is that the left is insincere in its values, and that principles of inclusion and unity are superficial forms of virtue signaling. White liberals might put a sign in their front yard saying IMMIGRANTS WELCOME, but they will abandon those immigrants at the first sensation of sustained pressure.

And in Trump’s defense, this has turned out to be true of many liberals in positions of power—university administrators, attorneys at white-shoe law firms, political leaders. But it is not true of millions of ordinary Americans, who have poured into the streets in protest, spoken out against the administration, and, in Minnesota, resisted armed men in masks at the cost of their own life.

The MAGA faith in liberal weakness has been paired with the conviction that real men—Trump’s men—are conversely strong. Consider Miller’s bizarre meltdown while addressing Memphis police in October. “The gangbangers that you deal with—they think that they’re ruthless? They have no idea how ruthless we are. They think they’re tough? They have no idea how tough we are,” Miller said. “They think they’re hard-core? We are so much more hard-core than they are.” Around this time, Miller moved his family onto a military base—for safety reasons.

The federal agents sent to Minnesota wear body armor and masks, and bear long guns and sidearms. But their skittishness and brutality are qualities associated with fear, not resolve. It takes far more courage to stare down the barrel of a gun while you’re armed with only a whistle and a phone than it does to point a gun at an unarmed protester.

Every social theory undergirding Trumpism has been broken on the steel of Minnesotan resolve. The multiracial community in Minneapolis was supposed to shatter. It did not. It held until Bovino was forced out of the Twin Cities with his long coat between his legs.

The secret fear of the morally depraved is that virtue is actually common, and that they’re the ones who are alone. In Minnesota, all of the ideological cornerstones of MAGA have been proved false at once. Minnesotans, not the armed thugs of ICE and the Border Patrol, are brave. Minnesotans have shown that their community is socially cohesive—because of its diversity and not in spite of it. Minnesotans have found and loved one another in a world atomized by social media, where empty men have tried to fill their lonely soul with lies about their own inherent superiority. Minnesotans have preserved everything worthwhile about “Western civilization,” while armed brutes try to tear it down by force.

No matter how many more armed men Trump sends to impose his will on the people of Minnesota, all he can do is accentuate their valor. No application of armed violence can make the men with guns as heroic as the people who choose to stand in their path with empty hands in defense of their neighbors. These agents, and the president who sent them, are no one’s heroes, no one’s saviors—just men with guns who have to hide their faces to shoot a mom in the face, and a nurse in the back.